Anti-war feminist writer and scholar Dubravka Ugresic (1949-2023) was one of Yugoslavia’s most esteemed writers before the disintegration of her country led to the collapse of her reputation. By 1993, her antifascist stance led to her being denounced, with four other women writers and academics, “as one of the five witches, the so-called ‘old hags’: feminists who ‘rape Croatia’, according to a tabloid.” Forced to live in exile, Ugresic labelled herself “transnational” and “post-national” and continued to write in Croatian. Her wickedly funny and surprisingly tender writing on dislocation, nationalism, exile, culture, and nostalgia is inextricably linked to her life and beliefs.

Lend Me Your Character is one of the books we feature in the June Book Box. Here, we take a brief glimpse at the life of its relentlessly brave and funny creator.

Dubravka Ugresic was born in 1949 in Kutina in Yugoslavia (present-day Croatia) to a Bulgarian mother and Croatian father. After majoring in Comparative Literature and Russian at the University of Zagreb, she went on to work there, successfully pursuing a parallel career as a writer. She won the prestigious NIN Prize in 1988 for Fording the Stream of Consciousness. Within three years, however, a new nation turned against one of its esteemed writers, eventually forcing Ugresic into exile.

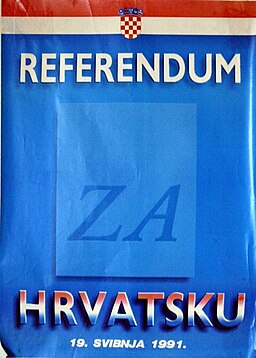

After a period of political and economic crisis, war broke out in 1991 in the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, splitting it apart. A series of separate but related ethnic conflicts, wars of independence and insurgencies, together called the Yugoslav War, continued for years until 2001, and resulted in the republics of Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia, Herzegovina, Montenegro, Serbia, and North Macedonia.

Franjo Tudjman came to power in Croatia, which declared independence in 1991. In stark contrast to her new nation’s nationalistic fervor stood Ugresic. She critically dissected Croatian and Serbian nationalism and took a firm antiwar stance, attacking the absurdity and criminality of war. The public’s reaction was swift and unforgiving: she was targeted by journalists, politicians, and her own colleagues. Despite her earlier popularity, critics refused to review her books and booksellers stopped displaying them. Ugresic, always acutely aware of the chauvinism and violence that automatically followed any outspoken woman, “came to understand first hand ‘what leads to collective lynching, mobbing, witch-hunt and burning people at the stake.‘” Socially ostracized and persistently harassed, Ugresic was forced to leave Croatia in 1993.

The Culture of Lies, an essay collection published in 1995 with Ugresic’s writings from 1991 to 1994, is both a reflection of her personal stance against fascism, nationalistic excesses and ethnic violence, as well as an honest dissection of how those in power manipulated the national and ethnic identities in the region. A New York Times article mentions an interesting story from the book:

She wrote about a small town that had once planted a grove of trees to honor the birthday of Josip Broz Tito, Yugoslavia’s longtime president. In the wave of Croatian nationalism of the 1990s, residents cut the trees down.

“They say they were removing ‘the last remnants of the communist regime,’” she noted. “The people who cut the wood down were the same people who planted it.”

The exile from her country heavily influenced all of Ugresic’s writing, as did the misogyny of the attacks aimed at her. “Well versed in the intimate link between the history of sexism and tired literary tropes,” Ugresic would later say this about being branded as a witch:

“I accepted it as an honourable name. I decided to take my broom and fly away.”

Ugresic first moved to New York, then Berlin, before finally settling in Amsterdam. She continued writing, refusing to accept all identities imposed on her. In Jasmina Lukić’s “To Dubravka Ugrešić, with Love“, she writes:

“Ugrešić ferociously fought for her right to be ‘nobody’, and to speak from the margins. Always taking a stance, she took responsibility for every word she uttered, deeply convinced that the first and most important task of a writer as a public intellectual is to speak truth to power. At the same time, she argued equally fiercely for her right as a writer to be known by her name only, and not by her ethnic origin or any other external labels. As a result, she remained an outcast of institutionalized national literary canons.”

Ugresic failed in her quest to be a nobody. Through her writing and her unwavering political stance, she became an icon for anti-war and anti-nationalist people everywhere, and especially from the former Yugoslav region. She developed her “patchwork literature” to explore the displacement and loss felt by many, to talk about the absurdity and tragedy of having been born in a country that no longer exists. Her writings also demonstrate the powers of Ugresic the scholar. Intertextuality comes naturally to Ugresic. She borrows words, sentences, literary tropes, moods and effects to create her patchwork literature. In her later years, she wrote about culture, consumerism, and individuality. Her criticism of Western consumerism is as sharp as her rejection of extreme nationalism.

By positioning herself as “transnational” or rather “post-national”, she championed the right of “authors not to recognize or respect ethnic and national borders, especially in cases where these are being imposed by force.” Or, as Charlie Connelly puts it in The New European,

“Ugrešić’s transnational viewpoint lent the book – and the rest of her work – a perspective rare among the writers of our continent: that we have an inalienable right not to belong.”

Ugresic went on to win the prestigious Neustadt Prize for International Literature in 2016 and she was frequently mentioned as a Nobel Prize candidate in the years before her death in 2023. Her insistence on not belonging pervades every story in Lend Me Your Character, and conversely created a sense of community and belonging in those like her. I leave you with the words of Vlad Beronja, one of her translators, which perfectly encapsulate her profound influence on those around her and on her readers:

“For many of us who had left the disintegrating Yugoslavia in the 1990s, ‘like rats deserting a sinking ship,’ with barely a tote bag or suitcase in hand—Dubravka was the poet of our newfound and embittered worldliness and the literary alchemist of our fragile memories. Since then, many of us have acquired new lives, new languages, new passports.

Some of us have even stopped thinking of ourselves as refugees altogether, buckling under the pressure of assimilation to secure our daily bread under a different sky. But with each new book, Dubravka reminded us again of that formative experience of migration, that dioptric of enduring alienation that no new passport can fully correct. And it is this defamiliarizing way of seeing the world from the margins that runs like a bright red, revolutionary thread throughout her virtuosic literary oeuvre.”