In 2024, I read exactly seventy books. There are several reasons for this high number: I have included books I have edited in the list; this is the year I discovered audiobooks; working at Boxwalla has introduced me to so many authors and new worlds that it has revived my once voracious appetite for reading. Mainly though, this was a year I sought the comfort of books over people, where I felt more than ever the need to escape into a book. I am not sure if I managed to “escape” successfully, since the books I read looked deeply at the world and at me and compelled me to keep thinking and feeling. I’ve not achieved much last year, but it was a good year for reading, if nothing else. Below, I list my top ten books from the seventy I read in 2024. I would love to hear your thoughts on these books, as well as recommendations from your 2024 reading. This year, I hope we all get to read books that move and change us.

The Door by Magda Szabo

I was introduced to Magda Szabo with The Fawn, featured in our August 2023 Book Box. The Fawn is a good book, and introduced me to Szabo’s proclivity to write about, in her words, “terrible women”. Abigail is Szabo’s most famous work and another of her novels I have enjoyed. But the effect of The Door is something else altogether.

The Door by Magda Szabo was the first book I read in 2024, and few books last year have been able to elicit the same satisfaction and depth of emotions that Szabo could. So, I was delighted when learned it was one of the books featured in our first-ever Boxwalla India Book Box.

There are no terrible women in The Door, only terribly human ones. At the surface, it is a simple, local story, exploring the relationship between Magda, a writer who has become to receive acclaim for her work after being censured (much like Szabo herself) and Emerence, her housekeeper. Szabo uses the simplest language, but her words plummeted straight into my depths. It will be difficult to find another novel that can so accurately portray female relationships as this one does, in all its emotional complexities, encompassing words, gestures, silence, and betrayals. The Door is a domestic story that feels like a suspense thriller. The betrayals in this book still haunt me. I think of Emerence regularly. I am afraid and excited to reread this book. I know I will cry through it. I know I will have to reread this every few years; The Door will forever stay with me.

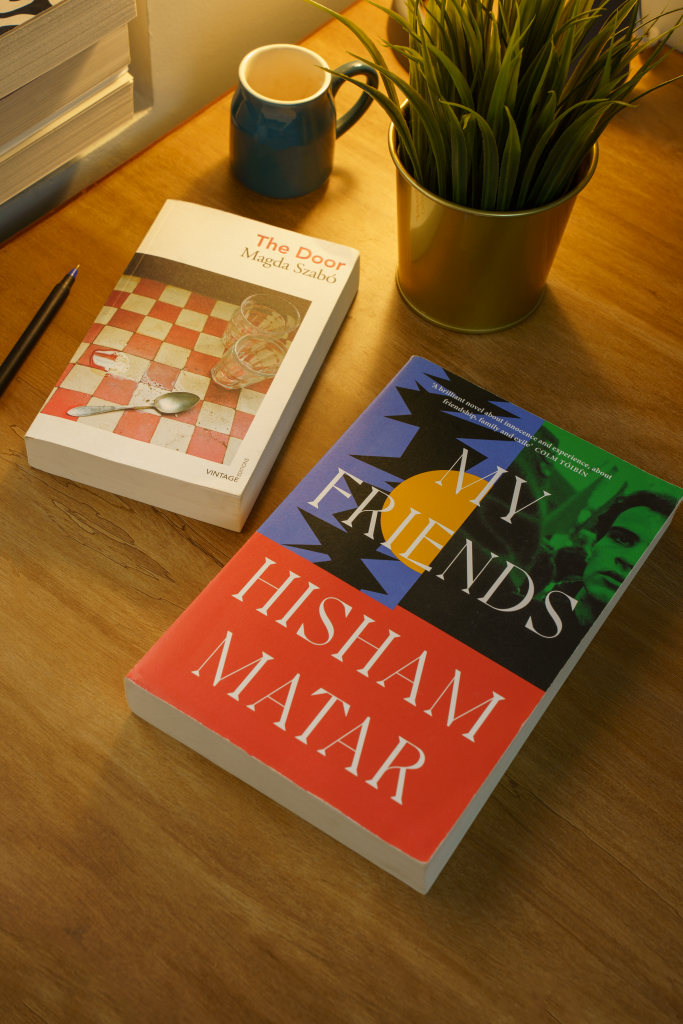

My Friends by Hisham Matar

Our first-ever Boxwalla India Box featured another book that made it to my top-ten list: My Friends by Hisham Matar. It is the story of three Libyan friends living in exile in London. Matar also weaves real-life event with fictional ones. Khaled, the narrator, and his friend are injured when they attend a protest against the Qaddafi regime in London. Their exile is a direct result of this.

This is a delicate, beautiful novel that chronicles the fleeting nature of everything. Time changes everything, and the Matar skillfully uses pacing for devastating effect: whole lives are sometimes condensed to a paragraph, while certain moments have pages dedicated to them. Like The Door, it emphasizes how fragile relationships are. Yet, in this book of exile, brimming with nostalgia and hope, it is the relationships that are sources of hope and life. It is the friendships that sustain the narrator and forces him to confront the many opposing ideas that constitute his life. Though time can damage or strain these bonds, they are still meaningful, their beauty lasting way past moments, embedded into our lives.

Pachinko by Min Jin Lee

Pachinko, first published in 2017, is already a classic. It is one of those rare successful literary novels, selling millions of copies and adapted into a TV show.

When a book is almost universally loved, I hesitate to pick it up, sure that it will not live up to the hype. The novel also is thick. This, along with its description as a “sweeping, four-generation saga” suggested that it would be a long, tough read. And as much as I love long reads and family sagas, I was convinced Pachinko would disappoint me. I couldn’t have been more wrong.

First of all, Pachinko is extremely readable. Picture a family or a friend group gathered around a fire, laughing and talking until one person, in this case Min Jin Lee, begins to narrate a story. Everyone else immediately quiets down, because this has all the signs of being a good story, and the narration invites you to listen in. By the end, you are so engrossed in the story and so invested in the characters that you don’t notice the fire has stopped burning, the sky lighter, while something inside you is changed.

Chinatown by Thuận

Our October Book Box featured Elevator in Sài Gòn by Thuận. Sourcing this book was difficult, as our book subscribers probably know. The publishing date moved, and with it, we had to push the box in which we’d feature this work. I am grateful Sandeep and Lavanya pushed through and ensured this book was in a book box no matter what, because it introduced me to a writer who effortlessly became a favorite. So, after I finished Elevator, I immediately borrowed Chinatown from the library. I have written about both books before but, in short, Chinatown is simply the thoughts of a woman while she is stuck in the Paris Metro. An abandoned package has been found in a train, and while her son sleeps on her shoulder and the package is checked, the woman begins to reflect on her life, taking us to Hanoi, Leningrad, and Paris.

Chinatown is a thin book, barely 200 pages. Yet, the narrator’s monologue is a world unto itself. Central to her thoughts is Thụy, her former husband who, after their son is born, leaves his family for Chợ Lớn, Saigon’s Chinatown. She searches for the reasons behind the choices Thụy, who is ethnically Chinese but living in Hanoi, has made. In doing so, she tries to make sense of her own life and the world she occupies. But the world she grew up in longer exists; she lives in a western, imperialist country that flattens her identity with all other Asians. Do we ever arrive at meaning through our fragmented selves, through the fractious world in which we live?

January by Sara Gallardo

We featured January by Sara Gallardo in our first Book Box of 2024. It is the first Argentine novel to represent rape from the survivor’s perspective and to explore the life-threatening risks pregnancy posed, in a society where abortion was both outlawed and taboo.The plot, of sixteen-year-old Nefer getting pregnant and unable to get an abortion, corresponded with what has been going on (and will most likely go on) in the US, and other parts of the world. As a woman reading this book in 2024, there is no distance you can possibly maintain from the story.

Nefer’s family is family is poor, estancia farmers in rural Argentina. She is raped at her elder sister’s wedding party by a drunk railroad worker. By the time the story begins, Nefer is already pregnant, already doomed. She tries to keep her pregnancy a secret from her devoted Catholic family and community, but it is a plan that is bound to fail. Even Nature seems to be against Nefer. Throughout January, and beyond its pages, Nefer is alone. You can read more about the book here.

Sara Gallardo is a fascinating figure herself, and I look forward to reading more (read: all) of her writing. Read more about the author here.

Hunger: A Memoir of (My) Body by Roxane Gay

What can I say about this book except I wept through it?

Roxane Gay is a feminist icon, her diverse oeuvre a testament to this. Still, her body is brought up, discussed and dissected frequently. It is impossible for a woman, especially a public figure, to not have her appearance be scrutinized and commented upon by, well, everyone.

I usually do not enjoy reading memoirs, something about them feels disingenuous to me. Hunger, however, feels like going through someone’s personal diary. Roxane Gay talks in intimate, vulnerable detail about her ongoing, contentious relationship with her body. Trauma leaves signs everywhere, including your body. Gay’s body is changed forever after an extremely horrifying incident in her childhood, and this memoir is her grappling with its aftermath, with what it means to exist in a body that is the enduring site of trauma.

I listened to Hunger, narrated by the author, and I found it impossible to not confront my own relationship with my body. Roxane Gay’s struggles with her body are vastly different from my own, but I too, like many of us, have a body I often despise, a body that has endured considerable violence and is still here, for some reason. Gay’s beautiful voice in my ears felt as if I was listening to a close, much wiser, friend, who insists:

I do not want pity or appreciation or advice. I am not brave or heroic. I am not strong. I am not special. I am one woman who has experienced something countless women have experienced. I am a victim who survived.

What Happened to Ruthy Ramirez by Claire Jimenez

Thirteen-year-old Ruthy Ramirez disappears one day after track practice. Twelve years later, her older sister Jessica is watching a reality TV show called Catfight, in which one of the contestants bears an uncanny resemblance to Ruthy. She tells her younger sister, Nina. Eventually, they decide to drive to where the show is being filmed to confirm their suspicions. At the same time, they’re dealing with their own struggles: Jessica manages raising a newborn with her demanding job at a hospital; Nina has been rejected from medical school after four years at college and is back home, working at a lingerie store. Their mother, Dolores, is still reeling from the disappearance of her second daughter and when she gets wind of what her other daughters are up to, she joins them on their trip with her friend, Irene.

A family of three sisters, tense car rides, family secrets and decades-long issues that simmer under the surface…What Happened to Ruthy Ramirez hit me so close to home when I least expected it. It is the story of a family of women and their complicated relationships with each other, in the background of a tragedy. Do we ever arrive at neat conclusions with family? Or do we continue to adjust and fight, reconcile and keep secrets, love and hate our families?

To Live by Yu Hua

To Live is arguably the most popular work of Yu Hua, one of China’s greatest living authors. It was originally banned in China but later named one of its ten most influential books in the last century. It was also was also adapted for the screen by Zhang Yimou, who read all of the book (then in serial form) in one night and resolved to make it into a film. Michael Barry was twenty-two and a senior at Rutgers University when he faxed Yu Hua for permission to translate his masterpiece. Since its publication, it has been read by millions over the world.

What is about this book that has had such an impact on people, you ask? The events and the characters in this book feel like allegories, the tale timeless. The novel documents the life of Fugui, and his transformation from the spoiled son of a landlord to a kind-hearted peasant. In some ways, this is a chronicle of Fugui’s endless suffering. Yet, To Live is an exhortation to keep at it, to live and to love.

Drive Your Plow over the Bones of the Dead by Olga Tokarczuk

I was an angry child. I raged against the various injustices, both real and imagined, that I felt plagued human existence from birth to death. I knew this rage was terrible; adults around me reminded me that children are supposed to be happy and that I hadn’t even experienced the world yet. So, over the years, I replaced my anger with other things, things that would numb the blunt hot prick of anger. In 2024, however, I’ve been relishing my anger; it makes me feel alive and do things. I realize now that anger does not equate to violence, but that it can propel me to action instead of hopelessness.

Olga Tokarczuk’s Drive Your Plow over the Bones of the Dead, set in a remote Polish village where dead bodies turn up in increasingly suspicious circumstances, was one of my most joyous reads this year. Of course, Tokarczuk’s writing is always a source of delight, and Drive Your Plow, while being a suspense thriller, is also a deeply satisfying fairy tale. This story has everything: a completely original yet unreliable narrator, environmental change, good guys and villains, animals and humans (with death touching both categories), and the poetry of William Blake, all of it smattered with plenty of rage.

A Children’s Bible by Lydia Millet

A Children’s Bible was my introduction to American novelist and Pulitzer and National Book Award Finalist Lydia Millet. The novel follows a group of twelve children on a vacation with their families at a sprawling lakeside mansion. Their parents are reckless, immature and largely unaware of their children’s whereabouts; the children are mature to a degree that is unsettling.

Major events in the book mirror important stories from the Bible. The mirror is either dusty or cracked, though, the reflection a distortion, a fragment, The children decide to run away when a destructive storm descends, embarking on a dangerous foray into the apocalyptic chaos outside.

This is a strange, dreamy book which I will have to read again to clarify my thoughts. The Biblical allusions lend it a prophetic quality, raising the horrifying question of what lies beyond The Revelations. It is, in fact, a prophetic book, calling attention to the climate crisis and highlighting generational divides which leave no room for a future of hope. A Children’s Bible is not an easy read, but it is a strikingly original story that is also over 2,000 years old.

Cover image: Photo by Eugenio Mazzone on Unsplash